There are few things in the world that I have dreamed of doing in my lifetime and one of those was to visit the remarkable Uffizi Gallery in Florence…these paintings demonstrate why it was well worth the visit.

The Uffizi gallery in Florence, the world-renowned Florentine museum, is filled with pictures selected from the very best of Italian painting. Its walls are hung with works by Giotto, Raphael, Tintoretto, and all the other great names associated with Renaissance artwork. But with such an abundance of high caliber art surrounding a visitor to the Uffizi, it is easy to become overwhelmed, unable to appreciate the virtuosity of each piece’s composition or the meaning being conveyed by the painter. It is necessary to linger a little longer than usual, to fully absorb the work’s visual impact and to look for specific parts which may point to its deeper significance. This essay is written for precisely that purpose. The five paintings I have chosen to discuss are The Coronation of the Virgin by Lorenzo Monaco, The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli, The Annunciation by Leonardo da Vinci, Lucrezia Panciatichi by Agnolo Bronzino, and Flora by Titian.

Perhaps the first piece I wished to note from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence was Monaco’s large altarpiece that depicts the intense moment just before Christ places a crown on the Virgin Mary’s head. Three golden arches form the main frame of the painting, dividing the human figures into three distinct sets: the holy pair, flanked by two groups of saintly onlookers. Within the picture, a blue rainbow curves across the bottom and a canopy frames the throne. Also dividing Jesus and His mother from Heaven’s other inhabitants are the armrests and over a dozen angels who stand about the throne, their backs to the saints around them. Monaco has made his backdrop a flat gold, typical of the period and representing the majesty of God. Other than the blue semi-circle on the floor and the canopy, the one architectural feature in the entire painting, there is little detail in the scenery. But despite this formalist approach to the backdrop, the figures’ realistic proportions and the use of perspective demonstrate that the artist wishes to create a convincing portrayal of Mary’s coronation.

Faces are rounded and even have lines and creases, while the rainbow gives some shape to the room and the canopy tapers back to show depth. In addition, Monaco’s light source seems to come from above and creates shadows beneath people’s chins, in the folds of the robes, and on the underside of the canopy. However, no one casts a shadow on the ground – either an unrealistic omission or an intentional symbol of divinity and immortality.

Bright, vibrant colors fill the Coronation, with the patron’s wealth on display in the gold and lapis lazuli used throughout the composition. Mary wears pure white with green and gold accents, while Christ’s clothing is the blue, red, and gold of royalty. All the saints are in festive array for this occasion. Even John the Baptist, usually restricted to dirty brown animal skins, has donned a red robe. These colors set the tone and give hints as to the painting’s theme, as do the relationships between the figures. Mary bows her head in gentle, dignified acceptance before Christ, and the angels focus piously on the throne. Monaco communicates respect for the Virgin and for her Son, scattering stars at their feet and using the rainbow as a symbol of divine faithfulness, but he does not box in the saints, whether above or below. The audience in Heaven’s throne room does not mechanically turn toward the throne and remain there like a group of inanimate statues: instead, the saints talk among themselves and even seem to be asking one another’s opinion of the event. While Monaco’s depiction of the coronation is beautifully reverent, he also inserts humanity into the picture and encourages questioning and discussion among his viewers, in this case all those who enter the church.

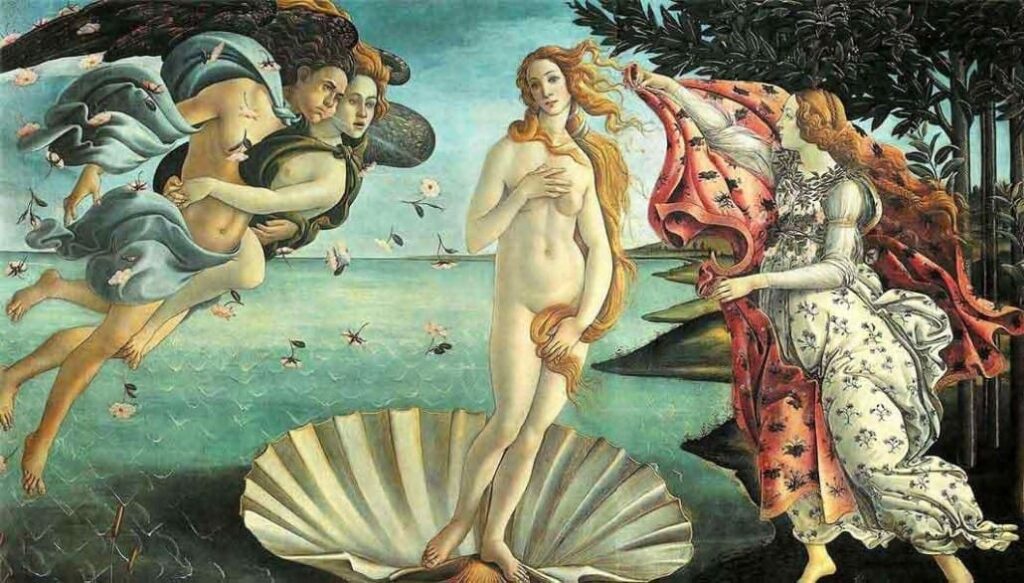

The subject of Botticelli’s visual masterpiece is startlingly different from the Coronation. In The Birth of Venus, the nude goddess arrives on a fertile island shore, blown by anthropomorphic breezes and riding on a scallop shell. The painting’s central figures are framed by the wings of Zephyrus and Aura, a spray of cattails in the lower left corner, and the gold-flecked meadow and trees. Venus herself stands in a triangular frame made up of the zephyrs, her shell, and a cloak held out by a graceful young woman on shore. A calm sea, cloudless sky, and detailed sylvan landscape form the background for the action, which is depicted with admirable realism. Botticelli’s human figures are well proportioned and on the whole anatomically correct. Besides the narrowing to a distant focal point, depth is created by light coming from the top left and the resultant shadows.

As for color, Venus and the girl on shore (who may be one of the three Graces) both have rich golden hair and the luxurious white skin associated with wealth. Gold is also used to accent wings, grass, and trees, but the predominant color scheme is the natural beauty of spring. The ocean which carries Venus to the dark island is a verdant blue-green; the cloak being offered to her ripples out in flowered pink folds. Roses fall from the sky, both a continuation of the springtime theme and a symbol of love. Venus is herself an emblem of love, and the winds which eagerly push her ashore sport angelic wings, perhaps a symbol of the heavenly power which drives them. Zephyrus and Aura appear to have been affected by the goddess’ power and embrace affectionately, and the Grace who waits on the island seems very glad to welcome this personification of love and beauty. Botticelli is a Florentine who can probably see parallels to his own city in the Greek myth of Venus. The goddess could conceivably represent Florence, a center of cultural rebirth as Italy emerged from its dark ages. With the artistic Renaissance in full swing, Botticelli may have chosen to depict Florence as a herald of enlightenment, sent by the divine will to illuminate everything around her.

Da Vinci’s Annunciation is a return to religious subject matter. The angel Gabriel has come to tell Mary about Jesus’ birth, and he kneels before her with his hand outstretched in blessing. She is not noticeably distraught or even surprised at his announcement. This may have something to do with the book lying open before her, for if she had been reading the Scriptures just prior to his arrival, her exalted state of mind would allow her to receive the news with serenity. The lectern serves as a frame for Mary, as do the gray blocks of stone which stand out against the blackness of the rest of the house. In the background, dark trees jut upwards into the bare sky. Flowers only bloom where Gabriel and Mary are, and even they do not add much to the stark backdrop. Da Vinci is known for his chiaroscuro work, and the lighting in the Annunciation is certainly no exception. Gabriel has arrived with the sun, the dawning of a new day, and the morning light produces sharp contrasts among the figures and their shadows. Besides emphasizing important areas like Mary’s face, this style of lighting adds to the depth of the picture. Objects are round and realistic, fabric folds are deep and soft, and the landscape tapers back to make a painting of perfect proportions.

Gabriel’s clothing is bright red, green, and white. Mary’s red tunic and pale complexion emerge from the dark folds of her heavy robe in a display of pure beauty, all the more important because da Vinci has chosen to omit supernatural depictions of glowing divinity. In fact, the entire painting has a realistic tone, without an overabundance of gold finery or a showy portrayal of the Spirit’s descent (although halos are evident). Mary is quite naturally surprised and even wears an expression of mild puzzlement, but the event seems like a rather everyday occurrence in comparison to some of the more dramatic pictures by da Vinci’s colleagues.

Bronzino’s Lucrezia Panciatichi focuses on one woman’s character rather than portraying several people within a specific narrative. As Lucrezia sits for her portrait, she appears very alert and interested in her surroundings. Her head is framed by a regal coronet of hair twisted with gold, while the nondescript chair beneath her is a mere convention and does not draw attention to itself. The architectural details in the backdrop, a column running up the left side and an arch over the woman’s head, are similarly cast into darkness. Nothing seems worthy of notice in contrast to Lucrezia, and the black background is only a foil to her brilliant gown and smooth skin. Bronzino has placed the light source in the top left corner, which emphasizes Lucrezia’s face, jeweled medallion, and open book. Shadows help to create roundness in her figure, a theme carried on by the chair’s curve and the faint spiral design at the top of the pillar.

The portrait’s color scheme is one of golden undertones, which permeate everything from Lucrezia’s jewelry to her fine complexion. Her sumptuous red dress coordinates with the pearls and precious metals she wears, and the rich vitality of the shade mirrors the intense expression in her eyes. Tapering down to wine-colored burgundy, the sleeves then accentuate her genteelly white hands. Bronzino hints at Lucrezia’s upright, unswerving personality by including the motto “Amour Dure Sans Fin” (Love Lasts Without End) on her necklace and selecting The Book of Daily Offices, full of prayers dedicated to the Virgin, for her to hold. A chair is not a resting place for this energetic, confident woman – if anything, it is a springboard. Though jewelry is necessary to show her prominent social position, Lucrezia’s natural poise and beauty relegates the golden chains around her neck to mere secondary ornaments. There are no artificial mannerisms in this portrait: as demonstrated in the realism of Lucrezia’s figure and the natural placement of her fingers, Bronzino is concerned with depicting the woman’s true character rather than a formalized version of her appearance.

The last painting I have chosen to admire from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence is Titian’s Flora, is another portrait. However, it differs widely from Bronzino’s work in its portrayal of a bashful bride reminiscent of the ancient goddess of fertility. In contrast to Lucrezia Panciatichi’s decided mouth and erect posture, Flora has an almost wistful look on her face and tilts her head to gaze away from the viewer. She is not fully contained by any border, except maybe by her own golden cascade of hair. The backdrop is a soft grey shadow, without any inanimate objects or architectural details to distract one’s attention from Flora’s exquisite figure. This is presented with consummate realism, the delicate shading on her flesh denoting depth and shape without any unnatural elongation or stiffness. The young woman’s rounded features are illuminated by light which comes from the left and emphasizes all points of interest, but not with the harsh brightness which would clash with Flora’s gentle, guileless manner. In accordance with the mythology underlying the portrait, Titian uses flower-like shades to bring Flora to life. Her ivory skin and pure white gown stand out against the mauve robe over her shoulder, not brilliant colors but subdued and radiantly lovely. The springtime blooms in Flora’s hand are symbols for her delicacy, fertility, and youthful promise.

Merely glancing at a picture does not require any mental effort, but neither does it give any reward to the viewer. To understand the greatness of a painting in the Uffizi gallery in Florence, one must take the time to ponder its composition and try to deduce its meaning. The five pieces I have discussed in this essay have much to say if they are only given a chance. As part of the Renaissance revolution, they all should be thoughtfully considered, closely examined to find what message the artist is sending through his work.

Thank you for reading this article about the majestic Uffizi Gallery in Florence! If you have any further questions about this topic please contact us.

I also hope it will inspire you to plan your trip to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.