With botany developing into a science the services of a drawing master of botanical art were required for the realistic and accurate portrayal of plants. At the same time, demand grew for pictures of flowers. From the 17th to the 19th century, the finest flower paintings were produced in France, Germany, Austria, Holland and England with Ehert, Bauer and Redoute being among the greatest drawing masters.

Walter Hood Fitch (1817-1892) was one of the most important British botanical artists of the 19th century. Introduced to botany by William Jackson Hooker, editor of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine and director of Kew Gardens, Fitch illustrated for Kew and other publications for 40 years producing some 9,000 drawings. Most famously he worked with Joseph Dalton Hooker, the most prominent botanist of the 19th century.

Before photography, the media used to draw plants and in flower paintings were

- Watercolour, first on vellum and later on hot-pressed paper

- Oil painting

- Wood cutting, etching and metal engraving

- Aquatint, mezzotint, stipple

- Lithography

How to Draw Plants according to Walter Fitch

Endersby’s Imperial Nature provides many insights on what Fitch and his partner, the famous botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, thought about the techniques and practices an artist should employ to draw plants or flowers. These were:

- Constant observation: According to drawing master of botanical art, Walter Hood Fitch, while colouring can be easily mastered, the only way for a botanical artist to acquire a correct eye for drawing is by constant observation.

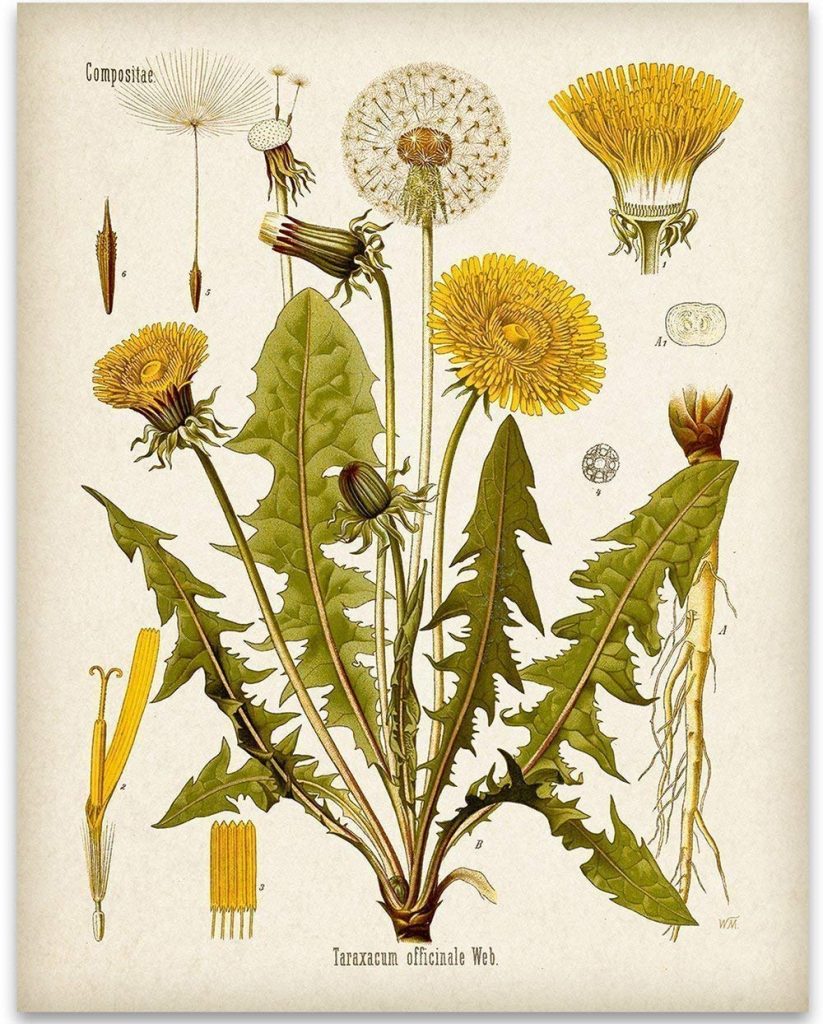

- Knowledge of plant anatomy: Fitch stressed that to draw plants and flowers and get the perspective right, the artist should have an understanding of plant geometry, a solid knowledge of plant anatomy and structure. Fitch himself was a master of plant dissection.

- Accuracy and bold outline: Accuracy was certainly important for flower paintings or botanical drawings. Hooker advised a field sketcher to make sure that he makes an accurate free bold outline: “Do not hold the pencil too tight nor press too heavy or hard, but learn to make free strokes”. Fitch was famous for his bold outline and free flowing strokes.

- Use other people’s sketches and dried specimens: Often Fitch never saw the plants he drew but worked instead from sketches provided to him by field artists or from dried plant specimens. A great drawing master of botanical art, Fitch was able to create flower paintings that looked lifelike from a series of flattened herbarium specimens. This he accomplished due to his deep knowledge of plant anatomy.

Finally as Endersby points out, before learning how to draw plants the Victorian student should have first learnt plant anatomy and classification: “drawing was only a learning process for those who already knew what to look for”. For flower paintings or for botanical drawings one needed a good, undamaged specimen; “the act of drawing was one point in a cycle of observation, mimesis, inscription and memorization”.

Thanks for reading this article! Please contact us if you have any further questions.